Categorizing Maltrieve Output

Wednesday, January 29, 2014 at 12:59AM

Wednesday, January 29, 2014 at 12:59AM UPDATE: @kylemaxwell has accepted the pull of this script into the main maltrieve repo!

*Note: For starters, we need to say thanks as usual to technoskald and point you in the right direction to the Maltrieve Code on GitHub.

Overview

We have posted Maltrieve articles a couple times in the past, but the capabilities of this application continue to amaze us so we thought we'd add to our past contributions. During our initial build of a malware collection box (malware zoo creation) we utilized a standard concept of running Maltrieve throughout the day using a cron job. As most simple things do, this became rather complex based on the fact that the Maltrieve delivery is not categorized in any method, so finding what you're looking for is.....shall we say.....difficult at best. This article discusses a categorization method to help you organize your malware zoo so that it is manageable.

If you would prefer this article in video format, it is provided as well:

Getting started

The box containing the malware repository is a standard Precise Pangolin Ubuntu Distro (12.04 LTS), so no big tricks or hooks here. Maltrieve is installed in a standard format, but a 1TB drive is being utilized to store the malware retrieved. The box has 3TB worth of space for later use, but for now we'll deal with just the 1TB drive. The malware repository is mounted at /media/malware/maltrievepulls. All scripts utilized (to include the Maltrieve python scripts) are located at /opt/maltrieve. Again, nothing flashy in any of this, so it should be easy for you to get your box setup quick if you'd like.

Running Maltrieve Consistently

To begin the build of the malware repository, we wanted to run the maltrieve scripts hourly so that the directory would fill with new and interesting malware consistently and quickly. This screamed “crontab”, so we fired up a terminal and ran sudo crontab -l and then sudo crontab -e so that we could edit the crontab. Our initial entry was as follows:

hourly python /opt/maltrieve/maltrieve.py -d /media/malware/maltrievepulls

@hourly echo "maltrieve run at: $(date) $(time)" >> /home/username/Documents/maltrievelog.log

This simply tells the system to run the maltrieve.py python script on an hourly basis and send the results to the /media/malware/maltrievepulls directory for safe storage. The second entry basically adds a little stamp in a file in my home directory so I can ensure the cron job is running every hour – you can obviously NOT include this statement if you don't see fit. In any case, we quickly noticed that the Maltrieve app was doing its job and we went about our business allowing the box to do what we asked. We quickly were swimming in malware and were ready to start analyzing to our hearts delight when we ran into the problem!

The Problem

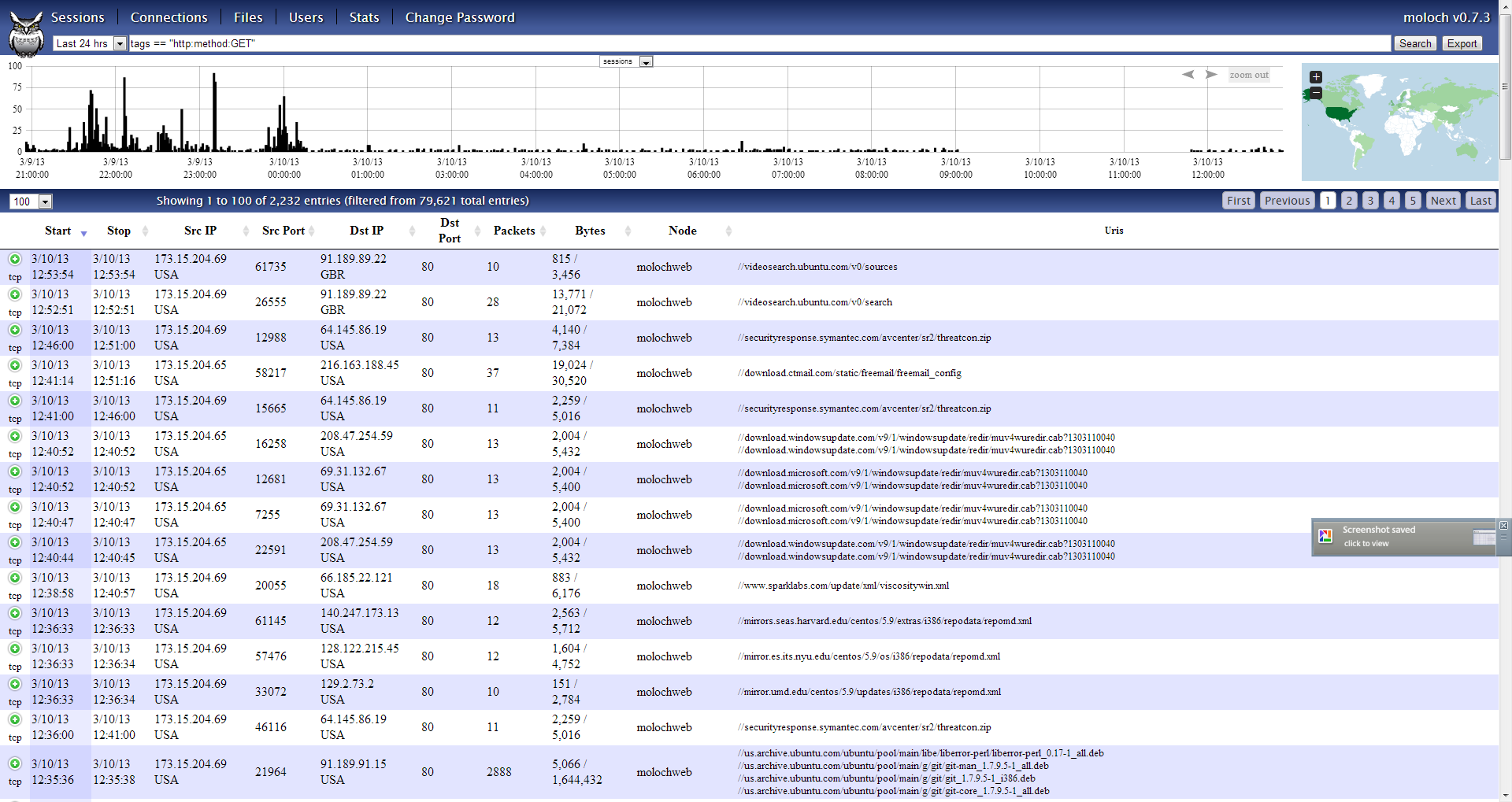

Maltrieve does exactly what it's told and it does it well – find malware from specific sites and put it in a directory of your liking. And it finds LOTS OF MALWARE if you keep running it as we did in hopes of having a massive store. However, the files are given a hashed name that has very little use to the human eye, and they are just plopped merrily into the directory you choose when you run the malware.py python script. It became quite tedious to run the file command on files that just “looked” interesting based on a hashed filename that gave little meaning to what it might be in terms of formatting, or even payload. A quick look could allow you to do some judging by filesize, but basic command line sorting, grepping, awking, and loads of other tools were needed to try and fix the problem. These methods were simply tedious and after we began to have hundreds of GBs of malware, it became downright no fun any more. The picture below will show you a glimpse of the problem.

Hardly the beacon of light for finding what you're looking for from your malware repository.

Running the file command on a few of these things starts showing some potential though because what you get from doing this looks like:

file 818fc882dab3e682d83aabf3cb8b453b

818fc882dab3e682d83aabf3cb8b453b: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows

file fd8fd6d345cb630d7f1b6926ce7d28b3

fd8fd6d345cb630d7f1b6926ce7d28b3: Zip archive data, at least v1.0 to extract

So here we find that we have 2 pieces of malware, one is a Portable Executable for a Windows box and the other is a Zip archive. This is a very nice start, but was just 2 needles in a large and growing haystack, and the manual effort was laborious and downright daunting.

Bash to the Rescue

As coders love to do, our answer was to take the awesome product Maltrieve and throw some more code at it. My initial thought was to extend the python script, but since I pulled this from a GitHub repository I didn't want to modify the code and then have to “re-modify” it later if things were ever changed or upgraded. My answer was to create a small Bash Shell script and run it to help categorize our malware repository. The requirements we set upon ourselves were to categorize the code into multiple directories based on the first word output from the file command and then further categorize that by separating the code by size. We decided that 0-50KB files would be considered “small”, 51KB-1MB would be considered “medium”, 1.xMB-6MB would be considered “large”, and anything larger would be considered “xlarge”. It's a rather brutish method but it's something and it seems to work nicely. So in the end, we would want to see a directory tree that looked something like this:

--PE32

----small

----medium

----large

----xlarge

--Zip

----small

----medium

----large

----xlarge

and so on and so on.

Since we set up our maltrieve pulls to run hourly we decided to run the bash script - which we so obviously named maltrievecategorizer.sh – to run on every half hour, which allows maltrieve to finish and then categorizes the latest findings. To make this happen, we cracked open crontab again with sudo crontab -e and added the following to the end of the file:

30 * * * * bash /opt/maltrieve/maltrievecategorizer.sh

which just says to run our bash script on the half hour of every day of the year, plain and simple.

The Bash Script

The maltrievecategorizer.sh bash script can be seen below. An explanation follows the script.

#!/bin/sh

smallstr="/small"

mediumstr="/medium"

largestr="/large"

xlargestr="/xlarge"

smallfile=50001

mediumfile=1000001

largefile=6000001

root_dir="/media/malware/maltrievepulls/"

all_files="$root_dir*"

for file in $all_files

do

if [ -f $file ]; then

outstring=($(eval file $file))

stringsubone="${outstring[1]}"

case $stringsubone in

"a") stringsubone="PerlScript";;

"very") stringsubone="VeryShortFile";;

"empty") rm $file

continue;;

*);;

esac

if [ ! -d $root_dir$stringsubone ]; then

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$smallstr"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$mediumstr"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$largestr"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$xlargestr"

fi

filesize=$(stat -c %s $file)

if [[ "$filesize" -le "$smallfile" ]]; then

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$smallstr/"

elif [[ "$filesize" -le "$mediumfile" ]]; then

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$mediumstr/"

elif [[ "$filesize" -le "$largefile" ]]; then

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$largestr/"

else

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$xlargestr/"

fi

fi

done

The first several lines simply create string literals for “small”, “medium”, “large”, and “xlarge” so we can use them later in the script, and then we create three variables “smallfile”, ”mediumfile”, and ”largefile” so we can compare file sizes later in the script. So far so good! The lines containing:

root_dir="/media/malware/maltrievepulls/"

all_files="$root_dir*"

for file in $all_files

do

if [ -f $file ]; then

do nothing more than set our root directory where our maltrieve root is and then run a loop against every file in that directory.

outstring=($(eval file $file))

Creates a variable called outstring that is an array of words representing the output of the file command. So using the file command output from above, the outstring array would have 818fc882dab3e682d83aabf3cb8b453b: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows in it. Each array element would be separated by the space in the statement, so outstring[0] would store: 818fc882dab3e682d83aabf3cb8b453b: and outstring[1] would store: PE32 and outstring[2] would store: executable and so on and so on. We are only interested in outstring[1] to make our categorization a possibility.

Our next line in the script

stringsubone="${outstring[1]}"

creates a variable named stringsubone that contains just the string held in outstring[1] so using the example above, stringsubone would now hold PE32.

The case statement you see next

case $stringsubone in

"a") stringsubone="PerlScript";;

"very") stringsubone="VeryShortFile";;

"empty") rm $file

continue;;

*);;

esac

fixes a couple problems with the file command's output. In the case of a piece of malware that is a Perl Script, the output that the file command provides is: a /usr/bin/perl\015 script. This may be helpful for a human, but it makes our stringsubone variable hold the letter “a” in it, which means we would be creating a directory later for categorization called “a” which is LESS THAN USEFUL. The same problem happens with something called Short Files where the output from the file command is: very short file (no magic) which means our stringsubone variable would hold the word “very” which isn't a great name for a directory either. The case statement takes care of these 2 and allows for a better naming method for these directories. It also allows for the removal of empty files which are found as well.

The next lines

if [ ! -d $root_dir$stringsubone ]; then

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$smallstr"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$mediumstr"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$largestr"

mkdir -p "$root_dir$stringsubone$xlargestr"

fi

simply tell the script to look in the directory and if a directory that has the same name as stringsubone does not exist then create it. Then create the directory small, medium, large, and xlarge within that directory for further categorization. Using the PE32 example from above, basically this says “if there's no PE32 directory in this root directory, create one and create the sub-directories small, medium, large, and xlarge within that directory. If the PE32 directory already exists then do nothing”.

The remaining lines look difficult but are simple:

filesize=$(stat -c %s $file)

if [[ "$filesize" -le "$smallfile" ]]; then

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$smallstr/"

elif [[ "$filesize" -le "$mediumfile" ]]; then

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$mediumstr/"

elif [[ "$filesize" -le "$largefile" ]]; then

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$largestr/"

else

mv $file "$root_dir$stringsubone$xlargestr/"

fi

fi

first we create a variable called filesize and then using the stat command, we store the file size in that variable. Then we find out if the file fits in our category of small, medium, large, or xlarge using if and elif comparison statements. Whichever comparison statement turns out to be correct is where the file is then successfully moved.

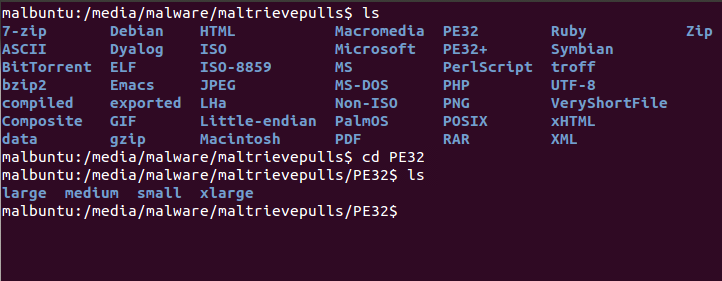

The results of this solution are in the picture below.

Conclusion

As you can plainly see, we now have the ability to quickly look for specific files in an easier fashion. If I am looking for a piece of malware that I know to be in HTML format that was over 50KB, but less than 1MB, I can easily roam to HTML->medium and a one-liner file command with some grepping and find what I am looking for. I'm certain there are other methods to go about this process and probably WAY better methods of categorizing this directory, so if you have some ideas please shoot them our way and we'll give them a try and see if we can help the community.